“My family couldn’t afford a headstone at the time of Grandma’s burial, but we can afford one now. What would I like to see carved into her headstone? ‘Here lies Augusta, mother, grandmother, and aunt. A beloved, beautiful, and regal soul.’”

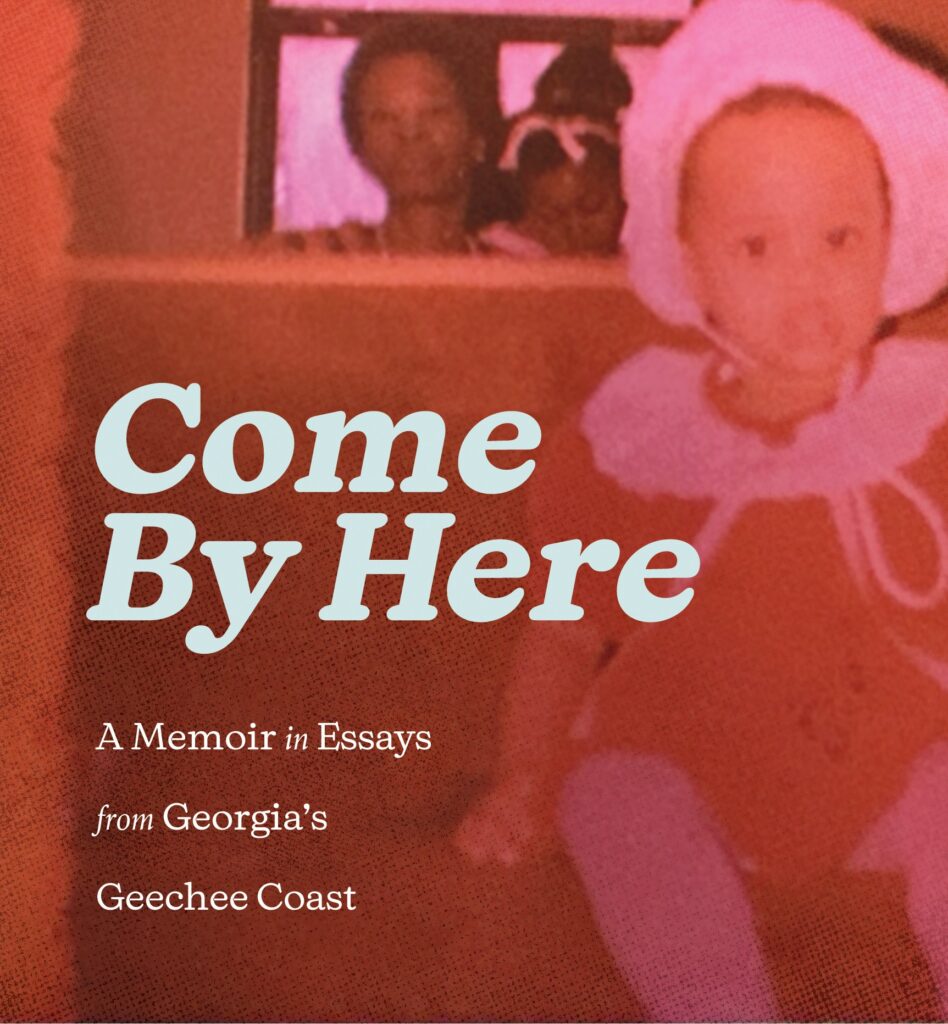

The final lines in the first chapter of Neesha Powell-Ingabire’s literary debut, Come By Here: A Memoir in Essays from Georgia’s Geechee Coast, illuminate the core discussions and tensions set forth by the Coastal Georgia native: family, place, and memory. Powell-Ingabire’s work encapsulates journalism, essays, and organizing in a way that “recovers her own history and the histories of her ancestors and their ancestral homes.” There is no easy route to creating a seminal work – let alone a memoir that centers one’s own story and the intimate connections that create a sense of self.

In a similarly candid conversation with The Peach Pit, Powell discusses the nuances of writing this book and recounts the anxiety, joy, and tears accompanying her throughout the creative journey. “There have been times when I felt like I could not continue,” she remembers.

But I did, and I did it for the people who are going to come after me and also the people who came before me – to honor their histories.” Unguardedly, Powell-ingabire admits that as the September 24 release from Hub City Publishers nears, “[I]t’s very nerve-wracking to know that all of my thoughts and feelings and my personal stories are going to be out there for the whole world to read.”

She continues, “That makes me so anxious and so nervous, but I know it’s important because people like me usually don’t get the chance to write the stories of our lives and publish those stories. I think it’s important to leave this as something that people like me look at in the future, even long after I’m gone, and they’ll know that people like them have existed forever.”

Through evocative first-person prose and in-depth reporting, Powell-Ingabire regales readers with stories of the South and the Georgia Coast—the beautiful, the beloved, the regal—meant to inoculate them with the region’s triumphs and ails.

Powell-Ingabire’s explorations prompt discussions about who is allowed to call a place home and whose history can survive. The story of a land is best told by its people, and they do their best to let the Georgia Coast speak for itself in all its mysticism.

How will the University of Georgia alum’s descendants portray her?

What will folks who identify as Black, queer, nonbinary, and disabled as Powell-Ingabire does think of the stories they tell? What will residents of the Georgia Coast who see themselves as Gullah Geechee people feel as they hear tales and read journalism about their community from a member who has worked to find their place through their work?

Audiences will read Come by Here and will answer for themselves the same questions Powell-Ingabire looks to explore.

The questions and answers from the interview with Neesha Powell-Ingabire have been edited for clarity and content.

***

Daniel Richardson, Managing Editor, TPP: I can only imagine the emotional roller coaster you must ride on when detailing the relationships and narratives of your life in this book and returning to those emotions as they were in time. What was it like for you to revisit some of those feelings in your writing?

Neesha Powell-Ingabire: Like you said, it was an emotional roller coaster. I would literally be sitting at the computer crying, just reliving some of those moments. A lot of times, I would go on my Facebook or something or look up old writings and things that would just take me back to different moments, and [it would] be very emotional, but also very cathartic. I think writing about yourself can be a very cathartic process – a very healing process – because I wrote things that I had never even told anyone before or even really spent time reflecting on before, and so to put them on paper and now to share them with the world, I’m proud of myself for having that courage to share my life with others.

DR: You talked about the catharsis that it was to write this memoir, and so one of the central tenets from your memoir, I gathered, was the relationship between you and your parents and your grandmother as well. You had some particularly poignant discussions and conversations throughout the work.

NPI: Oh, yes. And that’s one of the most nerve-wracking parts about publishing this because I know my parents will both read it. From me, there was so much ‘Should I share this? Should I write about it?’ There were so many things that I left out, simply out of respect for my parents, right? But I did share much more than I ever imagined I would ever share about my family life.

It was such an interesting process, writing down stories about these relationships and thinking about why certain things happened or how they impacted me. I talked about some of the differences that [my parents and I] have, but I didn’t want to make it come across as if they were villains or anything like that. Just like all parents did the best they could and had been through things in their lives, I didn’t want to paint them as villains. I did want to be real about it. Yes, l have differences with my parents, and we’re not always on the same page.

So many people can relate to that, and I wanted to be honest about that, but I also hope that they did not come across as villains because through writing this [book], I gained a lot of empathy for them and their lives and struggles. They weren’t perfect parents, but there are no perfect parents.

I hope that my writing about all these relationships, other people see their families in them and that there is no perfect family. All families have dysfunction, and that’s okay. We have our dysfunction, but at the same time, I do appreciate my parents for the different things that they have done for me and my life.

Writing about my grandma was emotional, and I just am very grateful for the time that I did get to spend with her. There are so many times now that I wish she were around to hear what she would say because she has so many funny sayings. This book is for her. This book is definitely for her because she always thought that I would grow up to be like this rich person, and I’m not. But she always had a lot of faith in me that I would make something out of myself. I hope this book honors her.

DR: The respect and reverence you have for your grandmother came across strongly in the book. But how you explored the relationship with your father was incredibly striking. There’s this scene you paint having a dinner with him after years of not being together. During this meeting, he revealed to you his struggles with mental health right around the same time that you were trying to cope with your own. When you remembered and went through the feelings of that conversation, what was going through your mind?

This book is for [my grandma]. This book is definitely for her because she always thought that I would grow up to be like this rich person, and I’m not. But she always had a lot of faith in me that I would make something out of myself. I hope this book honors her.

Neesha Powell-Ingabire

NPI: I had to really sit down and remember and look at old pictures and things like that. We did take some pictures that day. I did not include them in the book because I just wasn’t sure if he would want that. But I did have pictures from that day. I was looking at the pictures and just trying to remember them. And I remember I didn’t want to cry during that dinner; I could not hold back my tears. I didn’t boo-hoo cry, but it was silent tears. Writing that scene made me emotional again. It reminded me to have empathy for him and what he’s been through.

There are just things we don’t know about our parents when we’re growing up. And then, when we get older, they’re finally able to tell us the whole story and fill in all the holes from our childhood that we did not know.

DR: I promise to get off of the more moving parts of the book in this conversation, but even when talking about it now, in your voice, there’s still some emotion there. Am I correct in that?

NPI: Yeah, there is, especially because we’re getting closer to it being published and having [my family and friends] reading it. I know they’re going to read it. In graduate school, I would always ask visiting writers how they dealt with sharing these personal things about themselves and their families. It makes me wonder, how will I deal with it [when it’s my turn]? What if my family doesn’t like what I wrote? What is that going to mean for me? That’s where a lot of the emotion is coming from.

DR: A major part of the book focuses on your Gullah Geechee heritage and your heritage in the Sapelo Islands and the Savannah Coast of Georgia. Is that something you’re conscious about, not just your writing?

NPI: Growing up, [living on the coast] didn’t mean too much to me. I remember I had some old writings from middle school, and I would write, ‘One day I want to live in a big city, like Atlanta or New York City.’ I always had the idea of leaving [the region]. Truthfully, I didn’t think it was anything special because nobody ever told me it was special, and so I didn’t learn much about the culture or Black history there – that just wasn’t the focus at school. Now I know that so much of Black history is rooted there, and I think that’s something to be proud of.

That’s why I dedicated so much of my book to that place; it just hasn’t received much positive attention. It doesn’t get the respect it deserves — The Black history there. I think it’s starting to change some, and there are many people [on the Georgia coast], storytellers, cultural preservationists, and farmers [who are doing that work]. There is an emerging movement of folks who are really trying to reclaim Gullah Geechee roots and make sure that that culture and history are preserved.

There’s still so much poverty there. Brunswick, Georgia, is one of the poorest cities in the state while also being a majority Black city. There are still so many disparities and inequities there. With the murder of Ahmad Arbury, it does not have the best reputation in some places. [Hopefully], my book will shine a light on positive narratives about coastal Georgia, and when folks from there read it, hopefully they’ll feel a sense of pride.

Come by Here will be available for purchase from Hub City Publishers on September 24, 2024.

Daniel Richardson

Daniel Richardson is the managing editor of The Peach Pit. The formative years of his career were rooted in people-centered news coverage, particularly in the Atlanta and metro areas. His work has appeared in the Covington News, The Georgia State Signal, and others. After graduating from Georgia State University, he transferred his scholarship in Black, diasporic studies in movement journalism.

0 Comments