In August 2023, the South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control hosted nearly 70 corporate industry leaders, health officials, and economic developers in Augusta to discuss incoming regulations on particulate matter pollution, PM2.5, from the Environmental Protection Agency under then-President Joe Biden.

The EPA was weighing its options on lowering the standard emissions threshold of PM2.5 from 12 to nine micrograms per cubic meter (ug/m3).

According to an email to potential attendees, the call was to revive the Central Savannah River Area Local Air Quality Coalition and tackle the issue of strengthened air quality regulations in Augusta and the CSRA.

The Peach Pit obtained the message to coalition members Amy Curran of SDHEC sent before the meeting. The email encouraged attendance at the meeting because the EPA lowering and strengthening the National Ambient Air Quality Standards for PM2.5 “could have significant impacts on economic development and public health in the [CSRA]. The Augusta-Richmond County GA-SC Metropolitan Statistical Area may be the most impacted by a lower air quality standard.”

Attendees included Evan Adams from the EPA Region 4, Cal Wray of the Development Authority of Augusta, SC Republican State Representative for District 86 Bill Taylor; Robert Vandenmeiracker of TRC Environmental and the SC Chamber of Commerce; Bill Molnar, Augusta Regional Transportation Study Metropolitan Planning Organization chairman, and Lower Savannah Council of Government member.

Also in attendance were representatives from Solvay Specialty Polymers/SYENSQO and Graphic Packaging International – known major source industrial polluters in the Augusta area.

James Boylan, Chief official for the Air Protection Branch of the Georgia Environmental Protection Division, presided over the science and strategy of the meeting.

During the August meeting, air quality stakeholders convened at the North Augusta Municipal Building and virtually online for over two hours to discuss how strengthened air pollution standards and a potential nonattainment status could negatively impact industrial and economic projects.

“[Those zip codes] in Augusta are sick, and it can heal, but instead of giving it chicken soup, [industries] are going to make it drink a handle of whiskey.”

According to research released in February 2025, conducted by The Environmental Equity Information Institute, in conjunction with Healthy Communities Augusta and the Savannah Riverkeeper, five of the seven zip codes in the Richmond County, Augusta Area, are classified as environmentally and socially disadvantaged. E2I2 reports, “A census tract is considered disadvantaged if it meets more than one environmental burden and the associated socioeconomic threshold.”

The zipcodes 30901, 30815, 30904, 30909, and 30906 are exposed to the highest pollution levels in the area—and in some cases, the state and nationally. E2I2 found that the South Augusta area’s history of economic and political discrimination “results in greater exposure to environmental hazards.”

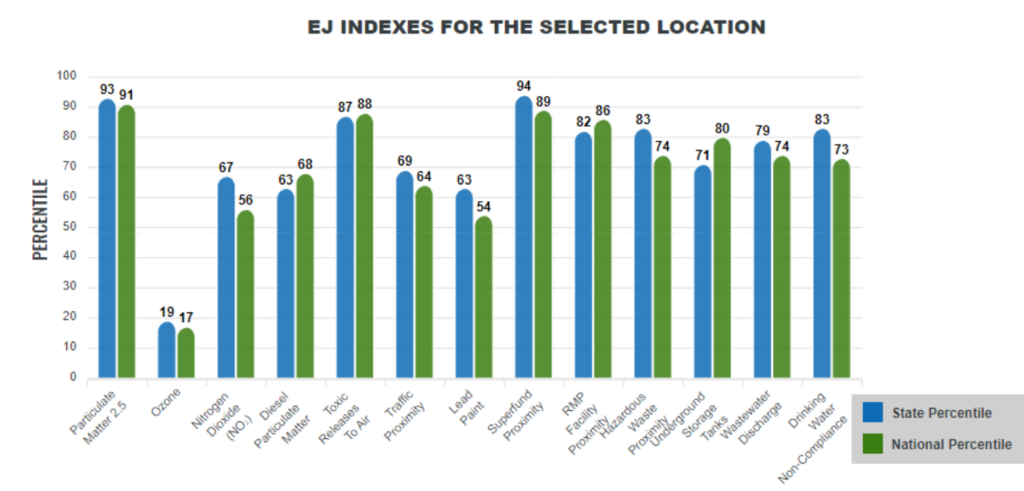

Using public data obtained from the EPA’s Environmental Justice Screener and the Climate and Economic Justice Screening Tool, E2I2 analyzed pollutant concentrations in the Augusta area to “identify which communities have the greatest environmental burden when considering the pollutants of concern and to understand if the environmental burdens differ by the social and demographic characteristics of the neighborhoods.”

Solvay’s EJ Screen data from 2025 shows that the heavily industrialized area of Augusta boasts an approximate population of 28,000 Georgians. 42 percent of these residents are considered low-income, with an average annual household income of around $23,000. The percentage of the population of people of color is 69, with the total percentage of Black residents at 61 percent.

The area ranks in the 93rd and 87th percentile statewide on the EJ Index for PM2.5 and toxic air release, respectively.

In 2024, the EPA officially set the standard limits annually for PM2.5 emissions at nine ug/m3. This standard also indicates that any 24-hour period that sees more than 35 ug/m3 of particulate matter in the air is considered “unhealthy.”

The E2I2 report notes that the World Health Organization recommends limiting annual levels to five micrograms and limiting them to 15 micrograms in a four-day period.

Data from CEJST illustrates that South Augusta and its disadvantaged zip codes see annual emissions of PM2.5 above both state and national averages – with an average of 9.58 ug/m3 emitted per year in the city’s most vulnerable areas alone. As of January 2025, the Trump administration removed CEJST and its data, created under an executive order by President Biden, from the White House website. The Harvard University Dataverse has since published the information and made it available for public download.

The State of Global Air concludes that long and short-term exposure to particulate matter disproportionately affects those who are economically disadvantaged, children, pregnant women, people over 65 years old, and residents with preexisting health conditions like asthma, bronchitis, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

SOGA suggests that “in people with heart disease, short-term exposure to PM2.5 can lead to arrhythmias, heart attacks, and even death.”

As area leaders vie for an increased presence of industry, Amy Sharma, the executive director of Science for Georgia, an organization focused on making science a focal point in public policy, worries that the environmental harm will only continue to worsen.

“The world can heal itself,” Sharma told TPP. “But say you have the flu and you’re feeling pretty crummy, and you decide to go to work today – it’ll take three times as long to feel better. However, if you had the flu and spent three days on the couch drinking chicken soup, you’d usually rebound faster because you’ve given your body time to heal.

[Those zip codes] in Augusta are sick, and it can heal, but instead of giving it chicken soup, [industries] are going to make it drink a handle of whiskey.”

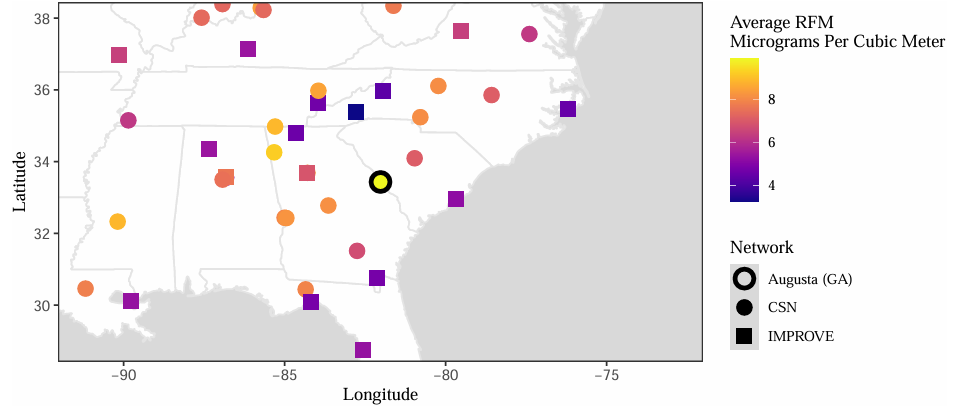

The Chemical Speciation Network, the air quality monitoring system at the University of California, Davis, uses available air quality monitoring systems to “support the implementation of PM2.5 NAAQS… and provide data to aid in health studies.” UC Davis collects samples of reconstructed fine mass in the air and reports the data year-over-year.

The daily RFM data for 2023 show a year in which, over a 12-month period, the ambient concentrations of matter in Augusta’s air read over 10 micrograms, with December 2023 reading levels of over 30 micrograms per cubic meter.

UC Davis’ information details the composition of the particulate matter in Augusta’s air: salt, soil dust, soot, organic matter, nitrates, and sulfates. There are natural emitters of compounds like wildfires, vegetation, and wildlife. However, the leading human causes of high PM2.5 levels remain chemical manufacturing, construction, vehicles, deforestation, and wood burning.

Augusta’s annual reading for 2023 ranked well above the median average of ug/m3 in the entire network monitoring air quality in the southeastern United States.

***

On December 20, 2024, the GA EPD announced the submission of a proposal to the EPA to remove 40 exceptional event demonstrations of PM2.5 exceedances from the Augusta area’s 2021 through 2023 calculation of their design values of the NAAQS standards. The events included 129 demonstrations of exceedances across the state, with EPD citing prescribed burns, Canadian wildfires, and July 4th fireworks shows as the primary causes.

The EPA defines exceptional events as “unusual or naturally occurring events that can affect air quality but are not reasonably controllable.” In 2016, the agency revised “the regulations that govern the exclusion of event-influenced air quality data from certain regulatory decisions under the Clean Air Act (CAA).”

“The CAA recognizes that it may not be appropriate to use monitoring data influenced by ‘exceptional’ events collected by the ambient air quality monitoring network when making certain regulatory determinations,” the EPA acknowledged in its final ruling.

The EPA suggests that “if a PM2.5 prescribed fire event satisfies the key factors for either” tier in the agency’s approach to illustrating casual relationships, the agency would concur.

A successful demonstration would also show elements of a conceptual model of the event, that there is a clear causal relationship, that the event is a human activity unlikely to recur, and that an air agency provides a public comment process.

Removing these events would lower the ug/m3 of PM2.5 that air quality modeling shows are emitted in their monitoring network, specifically the Augusta-MSA area. On February 7, 2025, GA EPD submitted the 23-page exceptional event demonstration document detailing its view of the causal relationship between the prescribed burns and other causes from Fort Eisenhower and the numerous exceedances of PM2.5 emissions from 2021-2023.

During the fall 2023 call, Chief Boylan alluded to the process of lowering the DV of PM2.5 through the process of submitting exceptional events, saying to the room of industry and economic leaders, “I don’t know what the conversation is at the federal level, but I do know that prescribed burns done at Fort [Eisenhower] can be part of the exceptional events, so we can remove those if it causes nonattainment. Those burns could be submitted to the EPA, and if the EPA concurs, the impacts of those burns could be removed.

If you remove enough, it could bring you below the standard; that’s a way to account for it. I agree there might be more coordination [with federal entities], but unfortunately, the states don’t have much authority over what goes on at military bases.”

According to the EPA, since the revision and adoption of the 2016 rules, there has only been one successful concurrence of an exceptional event demonstration showing causality to the exceedance of PM2.5 in the air because of prescribed fires.

The California Air Resource Board submitted nearly 70 pages of historical and contemporary data to the EPA to demonstrate that smoke from a prescribed burn in Grass Valley on April 20, 2021, spiked particulate matter levels in air quality monitors for a single day.

“If EPD has their way, and EPA agrees, Augusta will not be designated non-attainment despite the fact that the monitors, plain as day, are showing levels of PM2.5 that are unhealthy and above the standard.”

Throughout the 2023 meeting, representatives of industrial agencies and companies, including Rep. Taylor, all concluded that, based on Boylan’s presentation and likely their respective business interests, prescribed burns from Fort Eisenhower were the leading cause of particulate matter emissions exceedances as opposed to the heavily industrialized zone of South Augusta.

They agreed that these exceedances and more substantial air quality standards would discourage industry from settling in the area.

“I’m looking at everything available to us, not to have any areas designated for nonattainment, [using] bias adjustment, or exceptional events; we’re going to look at every tool in our toolbox,” Boylan attested.

I agree it’s not fair to penalize the industry for something they’re not really the main contributor [to].”

In an April 2024 follow-up meeting with coalition members, Boylan presented a swath of data supporting and demonstrating how removing the exceptional events would allow nonattainment areas to meet, at least visually, the lowered NAAQ standard.

A portion of the data suggested that lowering the standards would hamper industry’s efforts to grow in the area; GA EPD would have to go further and remove historical background concentrations to allow more room for projects to maintain their emissions standards.

As of December 2024, federal rules require that any existing industry pollutant sources undergoing major modifications are subject to the prevention of significant deterioration or PSD regulations.

PSD, the EPA says, is to, in part, “insure that economic growth will occur in a manner consistent with the preservation of existing clean air resources, and assure that any decision to permit increased air pollution in any area … is made only after careful evaluation of all of the consequences of such a decision.”

“[Meeting the standard] leaves no headroom for new industry to come in and build and have emissions, ” Boylan alerted the room. “So what we would like to do is remove different days and exceptional events to get us below nine ug/m3, to give us the headroom to allow industry to come in, so if we get the [values] down to seven, it actually gives us the headroom for industry to come in and expand.”

According to Boylan, during this meeting, the EPA leaves the “removal of data for background PSD purposes to the permitting authority.”

GA EPD serves as the state’s authority for air permits and is planning to remove 1,256 exceptional events, including 88 in Augusta, according to the presentation deck TPP reviewed.

Relatedly, in February 2025, Solvay/SYENSQO submitted a draft permit to EPD to expand its facility’s operation, including introducing its novel Project Sarsaparilla. This industrial process is said to increase the capacity to produce polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF), a plastic used in the production of Electric Vehicle batteries. The federal government granted the facility $178 million for this effort through the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law to buttress the country’s transition to a majority EV consumer base.

South Augusta Residents and local environmental advocates in the 30906 zip code question the permit’s lack of transparency regarding Solvay’s potential to increase its emissions.

Initially classified and operating as a Title V Major Source pollutant, the facility’s draft permit asks EPD to consider it a minor source, allowing the manufacturing plant to skirt implementing the best available control technology to regulate its emissions.

According to the chemical manufacturing plant’s draft permit, the company predicts an increase in the facility’s PM2.5 emissions by 19.4 tons per year – 10 tons per year is the threshold for major modifications. Additionally, Solvay/SYENSQO expects to increase its total annual Nitrogen Oxide (NOx) emissions to 98.3 tons per year, just under two tons shy of the major source pollutant designation threshold.

GA EPD is expected to decide on the permit status before the summer of 2025.

“If EPD has their way, and EPA agrees, Augusta will not be designated non-attainment despite the fact that the monitors, plain as day, are showing levels of PM2.5 that are unhealthy and above the standard,” Southern Environment Law Center attorney Patrick Anderson said in an interview with TPP.

The public should know that they will have an opportunity throughout the year, but primarily in the fall around October, to weigh in on EPA’s determination of whether Augusta and other places in Georgia should be considered in nonattainment.”

In January 2025, SELC attorneys submitted legal comments to Boylan and GA EPD regarding the draft exceptional events proposal.

In 2016, the EPA acknowledged that per the CAA, for there to be sufficient evidence of an “exceptional” exceedance or violation of the NAAQS, an air agency must illustrate that “a clear causal relationship … exist[s] between the measured exceedances of a national ambient air quality standard and the exceptional event to demonstrate that the exceptional event caused a specific air pollution concentration at a particular air quality monitoring location.”

The agency stipulated, “[s]howing that an event and elevated pollutant concentrations occurred simultaneously may not establish causality.”

In the legal comments reviewed by TPP, SELC attorneys note that the exceptional events provision’s initial purpose was to supplement “reasonable controls” of emissions instead of being used as a singular regulation instrument.

“Given the widespread and repeated impacts of smoke from prescribed fires on air around Georgia, EPD should have taken steps since 2008 to ensure the Georgia [Smoke Management Plan] was sufficient,” attorneys explained in the legal comments.

Likewise, additional measures should have been undertaken between 2021 and 2023 to address the problem of prescribed fire smoke … the recurring impacts of prescribed fire smoke should not be disregarded as exceptional events.”

According to Boylan’s April 2024 presentation, the GA EPD plans to “keep submitting 50-100 exceptional events, every year forever,” to maintain attainment with the standard.

However, the legal memo sent by SELC identified a key discrepancy in this methodology, pointing out that “to qualify as an exceptional event, emissions resulting from human activities must be ‘unlikely to recur at a particular location.’ Attorneys continued, “But prescribed fires are, by definition, initiated by human activity at a scheduled interval.”

In the document responding to public comments on the exceptional event proposal, GA EPD responded to this interrogation, saying, “[We do] not think it is reasonable to expect each demonstration to include actual, site-specific information regarding the frequency of prescribed fires at thousands of specific locations.

Since information was not available on the actual prescribed fire interval for specific tracts of land, [we] calculated an average fire interval for each county.”

***

During the clean air coalition kickoff meeting in 2023, the question of whether GA EPD air modeling could “show SC contributing to the Ga monitoring problem” in terms of preparing the list of recommended counties to be named either meeting or not meeting the NAAQS standard.

Since 2013, the EPA has employed a five-factor model for analyzing final determinations of attainment and nonattainment of regulatory standards: Air Quality data, Emissions and emissions-related data, Geography and topography, and jurisdictional boundaries.

Jurisdictional boundaries “identify the planning and organizational structure of an area to provide insights into how air quality planning and enforcement in a potential nonattainment area can be carried out.”

Counties, MPOs, existing nonattainment areas, and air districts are all examples of jurisdictional boundaries.

“If you have a monitor that’s over, that county is usually brought in, and you start looking at other counties to see if their emissions contribute to that violation. If you determine that they don’t, we would not recommend that they be included,” Boylan answered.

In theory, you could have just one county be in nonattainment; Richmond County could be the only county. It could be two counties; it could be three counties.”

GA EPD recommended to EPA in 2024 that all counties in the Augusta area be considered in attainment of the 2024 standards.

“It’s just this giant shell game,” a local Augusta environmental activist told TPP. “It’s been really depressing because Augusta has a long history as a chemical manufacturing hub.

We thought that was in our past, like [with what happened] with DuPont. DuPont did a decent amount of damage here, as did a bunch of others. [In Augusta], we’ve been the largest emitter of benzene in three states and the largest amount of toxic releases in the United States – all of that’s been here.”

Richmond County has suffered extensive environmental neglect. Dating back to the early and mid-20th centuries, the residents of South Augusta endured contaminated water from industrial runoff, a lack of infrastructure to deal with flooding and heavy industrial zoning.

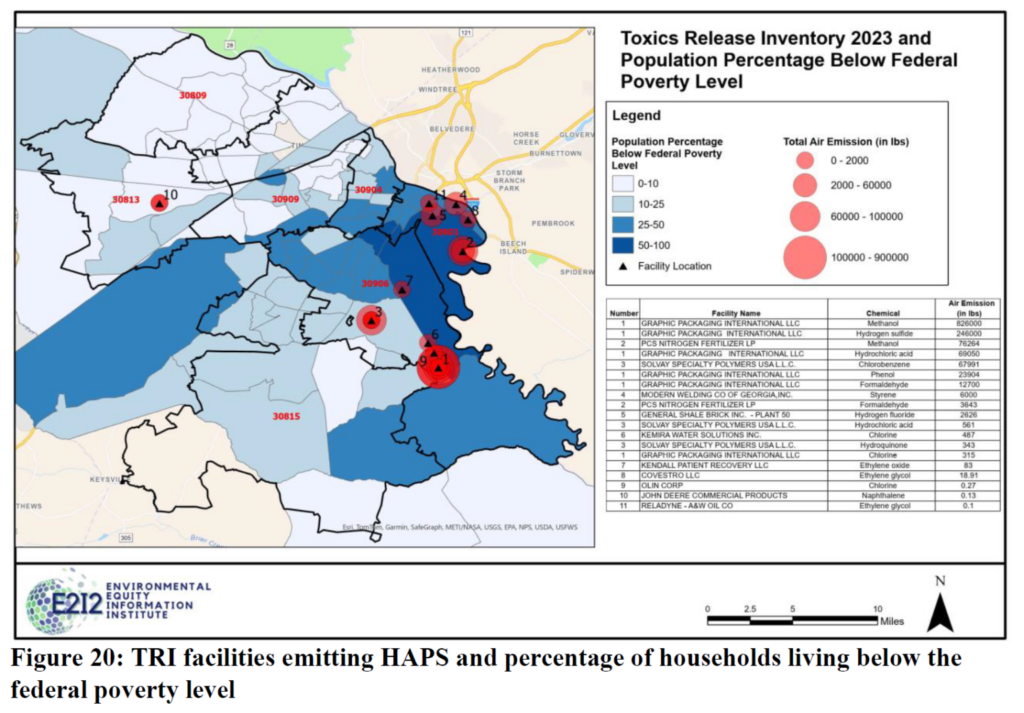

According to data from E2I2 and the EPA’s toxic release inventory, 16 facilities, including Fort Eisenhower, located in Richmond County’s disadvantaged zip codes, collectively emit over 140,000 pounds of harmful chemicals.

Solvay is the largest annual emitter of toxic chemicals in the area, emitting over 35 tons of chlorobenzene, a chemical linked to cyanosis, numbness, and muscle spasms, according to the EPA.

Residents like Cassandra Loftlin of Healthy Communities Augusta call the fight for public health justice in the area “generational.”

“People that fall in those [historically] redlined areas have the odds stacked against them,” Sharma explains. “If you were in a redlined area, it was pretty easy just to come in put in a tire factory or the turpentine factory, and because no one cared about the people that lived in those areas, it was easy just to go in and get it done.

Moving forward to today, you’ve got a bunch of people living in poor environmental conditions. They’re fighting an uphill battle because they’re already living with all of these facilities that have been there historically, and because they are in semi-industrial areas, no one is paying attention.

That’s where heavy industry has always gone, so it’s this historical snowballing effect.”

Update: This article was updated on April 16th to fix an error. To submit errors for fact-checking, please reach out to frontdesk@gapeachpit.com.

Daniel Richardson

Daniel Richardson is the managing editor of The Peach Pit. The formative years of his career were rooted in people-centered news coverage, particularly in the Atlanta and metro areas. His work has appeared in the Covington News, The Georgia State Signal, and others. After graduating from Georgia State University, he transferred his scholarship in Black, diasporic studies in movement journalism.

0 Comments