South Augusta residents and communities in the surrounding Central Savannah River Area are sounding the alarm against a planned expansion of the Solvay/SYENSQO plant that has operated there since 1984.

In 2024, the chemical manufacturing plant drafted a permit application to the Georgia Environmental Protection Division seeking approval to make significant modifications that would ultimately “supply polymer to the rapidly growing advanced battery production industry” through their new production process of manufacturing polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF), a material used in the production of Electric Vehicle batteries.

The company’s claims of providing a cutting-edge product to help streamline the United States’ shift to EV are coming at the cost of the area’s environment, according to everyone who has spoken with The Peach Pit for this reporting.

Hyde Park, a historically Black neighborhood built in the wake of the Jim Crow South, has a history rooted in resistance to over-pollution, contamination, and continued divestment at the expense of environmental justice. “There’s not one person in South Augusta that we know that has not been touched by cancer,” Cassandra Loftlin of Healthy Communities Augusta told TPP.

“Either they have cancer, or an immediate family member has cancer. We got folks that are getting cancer in their 80s, but then we’ve got folks that are getting cancers in their 20s and 30s.

It’s multigenerational because people have moved there and settled there.”

Beginning in the 1990s, five decades following its founding, the community of Hyde Park dealt with a string of sickness that families traced to the unusual amount of lead deposits in the soil.

According to data from the United States Environmental Protection Agency, Augusta has among the worst air quality metrics in the state. The 30906 zip code has some of the heaviest concentrations of toxic chemicals compared to the rest of the state.

South Augusta is surrounded by several air pollutant industries that emit over 5 million pounds of emissions annually, with Solvay landing in the top three emitters in the area.

In concert with Healthy Communities Augusta, the Environmental Equity Information Institute (E2I2) analyzed public data to investigate the socio-economic conditions of seven zip codes in the Augusta area, specifically the most vulnerable zip code, and where Solvay operates, 30906.

E2I2 used the EPA’s Toxic Release Inventory of 770 toxic chemicals, a database used for corporations to self-report chemical emissions over a year, to highlight the emissions levels in specific zip codes around industrial facilities.

According to the TRI data, Solvay emits several chemicals into the air, including nearly 70,000 lbs, or nearly 30 tons, of chlorobenzene, annually.

The cluster of industrial plants analyzed by E2I2 are all located in the area of Augusta that has the highest concentrations of Black residents, residents living below the poverty line, and residents who have the highest rates of asthma and respiratory disabilities in the state.

Science for Georgia, a nonprofit organization in the state advocating for the use of science in public policy, cites Richmond County as having a life expectancy of up to four years less than the state average.

“Even though we have high rates of cancer, high rates of asthma, that was one of the things that the community asked after the [public comment] hearing, how do we prove that our sickness and illness comes from a particular place,” Lofltin posited when asked about Solvay’s and others’ responsibility for the community’s circumstances.

“We can say this group of people lived here in this area, near Solvay, for this particular amount of time, but to prove it was actually them when we have so many other polluting industries in the area is difficult.”

These data points illustrate how a region in the state seeks relief from an environmental health problem harming generations of families in the CSRA.

Historical Environmental Threat

Solvay has a documented history of harming local U.S. communities and environments. The New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection filed a complaint in 2020, alleging that for decades, the facility emitted thousands of pounds of pollutants into the air while refusing to comply with requests to investigate the impact of its contamination by way of “forever chemicals” on the state’s water supply. The Department stated in the lawsuit that “there was no more concentrated finding of perflourononanoic acid – a type of PFAS – in the [s]tate as at and around the Solvay site. After three years of litigation and legal back-and-forth, the chemical manufacturing plant settled for an extraordinary $393 million in 2023.

Several other cases exist where Solvay has skirted or outright ignored environmental regulations.

“Like with all settlements, Solvay doesn’t admit guilt or anything like that. But they did agree to pay almost $400 million, which is a massive penalty in the environmental world,” says Patrick Anderson, Staff Attorney for the Southern Environmental Law Center, speaking on the case in New Jersey.

“[Solvay’s actions] were a serious set of violations, and it impacted water and soil, and it impacted people. It doesn’t bode well for the company’s expansion in Augusta – it’s cause for concern.”

Most recently, in February 2025, the city of Savannah, Ga, filed a complaint against 50 companies and their respective subsidiaries operating in Georgia and South Carolina, including Solvay and its operating subsidiary, Cytec. The complaint alleges that “the defendants have continuously caused and permitted PFAS-contaminated waste streams to discharge into the Savannah River” and into the water source that Savannah distributes to its residents.

The Transparency Issue

“[Solvay’s application] redacts a whole lot of information that it shouldn’t redact, and EPD should not have allowed that,” Anderson says. “Under the Clean Air Act, you cannot redact or omit emissions data. Data that tells the public what the facility emits can’t be considered confidential.

In this instance, a bunch of it was, and that made reviewing it from the public perspective pretty much impossible.”

During the public opinion period that lasted through February, Augustans voiced their concerns regarding Solvay’s plan to expand its operation and the draft permit’s lack of transparency.

The SELC, on behalf of several Augusta community members, including Historic Spirit Creek Baptist Church, Healthy Communities Augusta, Savannah Riverkeeper, and others, submitted a 20-page legal argument comment outlining the many concerns they identified within the draft permit application.

In its application, Solvay redacts information it classifies as “confidential, trade secrets, or proprietary information.” The company conceals a large swath of data—including emissions data—of its proposed new “Sarsaparilla Process” for producing PVDF, intending to protect industry and process information.

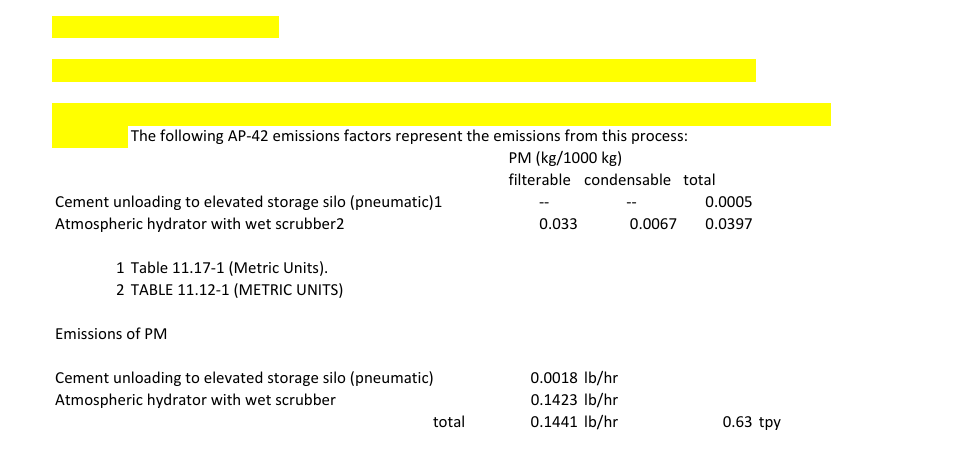

SELC, in its memo, notes that the emission data Solvay does provide and that Georgia EPD approved, using assumed or anticipated emissions averages, is either insufficient or incorrectly applied to measure the company’s status as a minor or major source pollutant.

The EPA rules suggest that state environmental protection divisions use “potential to emit” (PTE) to diagnose emission status because, according to the SELC memo, “PTE is a ‘worse case emissions calculation,’ and is markedly different than ‘anticipated actual’ emissions.”

EPA defines PTE as the “maximum capacity of a stationary source to emit any regulated air pollutant under its physical and operational design.”

Any facility that emits more than 100 tons per year of one regulated air pollutant or 10 tons of at least one hazardous air pollutant, like chlorobenzene, is considered a Title V Major Source under the agency’s rules.

According to the permit’s Maximum Anticipated Actual Emissions data, Solvay is expected to increase its total annual emissions of Nitrogen oxide (NOx) to 98.3 tons per year, just under two tons shy of the major source threshold.

The legal memo from SELC continues to identify that the potential to emit can be mitigated by “enforceable operating limits,” but the Solvay draft permit fails to include any detailed plans for such limits.

The environmental and health effects of NOx are tied to respiratory issues and increased hospital visits, with extended exposure time potentially leading to the development of more serious conditions like asthma, according to information released by the EPA.

In its review of the Solvay Permit, GAEPD granted the facility status as a minor source, considering the outlined expected emissions appropriately above the threshold for classification as a major source.

“This is a really large petrochemical plant operation, and they’ve got more than 400 units that emit air pollution,” Anderson told TPP. “Despite the size of it, the company and the state are claiming it’s only a minor source of pollution, and by claiming it’s a minor source, they don’t have to do a whole lot more rigorous and protective things like assessing air pollution control technology or assessing their impacts on ambient air and the air people breathe.”

GAEPD responded to TPP’s questions about transparency and concerns about emissions status in an email.

“EPD is currently reviewing and responding to the public comments received and will be publishing the responses in a Response to Comments document,” EPD officials told TPP in an email. “[Questions regarding pollutant source status] will be addressed in the Response to Comments document.

The next step following the Response to Comments document will be the final permit decision.”

The U.S. Department of Energy and its Office of Manufacturing and Energy Supply Chains, in 2023, granted Solvay $178 million to help offset costs to upgrade its facility as a part of the U.S. Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, also known as the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law according to a press release from the company. According to the DOE, the funding was provided to corporations across the country to help invest within the EV battery supply chain, increase domestic battery manufacturing, and create energy-focused jobs within communities.

Solvay’s slates the timeline for completion and to be fully operational by 2030.

Loftlin explained to TPP that even though Solvay claims to have plans to hire from the community, she isn’t optimistic about sacrificing the community for those plans.

“If you come into an area that’s disadvantaged, people may have a high school diploma, may have some college, but definitely don’t have that next level of engineering, training and energy background that’s needed to produce EV batteries,” Loftlin said.

“[Solvay] can say all they want, ‘We’ll hire from the community first,” but people from the community apply, and they end up getting jobs that are the average kind of blue-collar jobs, janitorial, culinary, and utility. So the real boost – the big paying jobs – don’t go to folks in the community.

What we’re asking for, if we ever have the chance to sit down and talk with them, is not only that you ‘hire from the community’ or the neighborhood first, but you make pathways for people to get that job training.”

Anderson and the SELC support the effort to create jobs within the energy sector but would like to see GAEPD review Solvay’s draft permit more carefully so that the public is fully aware of the cost-benefit.

“I’m always comparing [environmental protections] state to state, and Georgia does a fairly decent job in terms of writing permits,” Anderson said. “Frankly, I was surprised by this permit. And I even said so in my oral comments that they got this one so wrong.

I’m hopeful that they’ll recognize the problems we raised and fix them. I think it’s totally possible they don’t, but I’m cautiously optimistic.”

Update: This reporting was updated on Feb. 26 to include comments from the Georgia Environmental Protection Division.

Daniel Richardson

Daniel Richardson is the managing editor of The Peach Pit. The formative years of his career were rooted in people-centered news coverage, particularly in the Atlanta and metro areas. His work has appeared in the Covington News, The Georgia State Signal, and others. After graduating from Georgia State University, he transferred his scholarship in Black, diasporic studies in movement journalism.

0 Comments