For interconnected struggles, the Summer of Resistance is a time to create a way forward for Georgia.

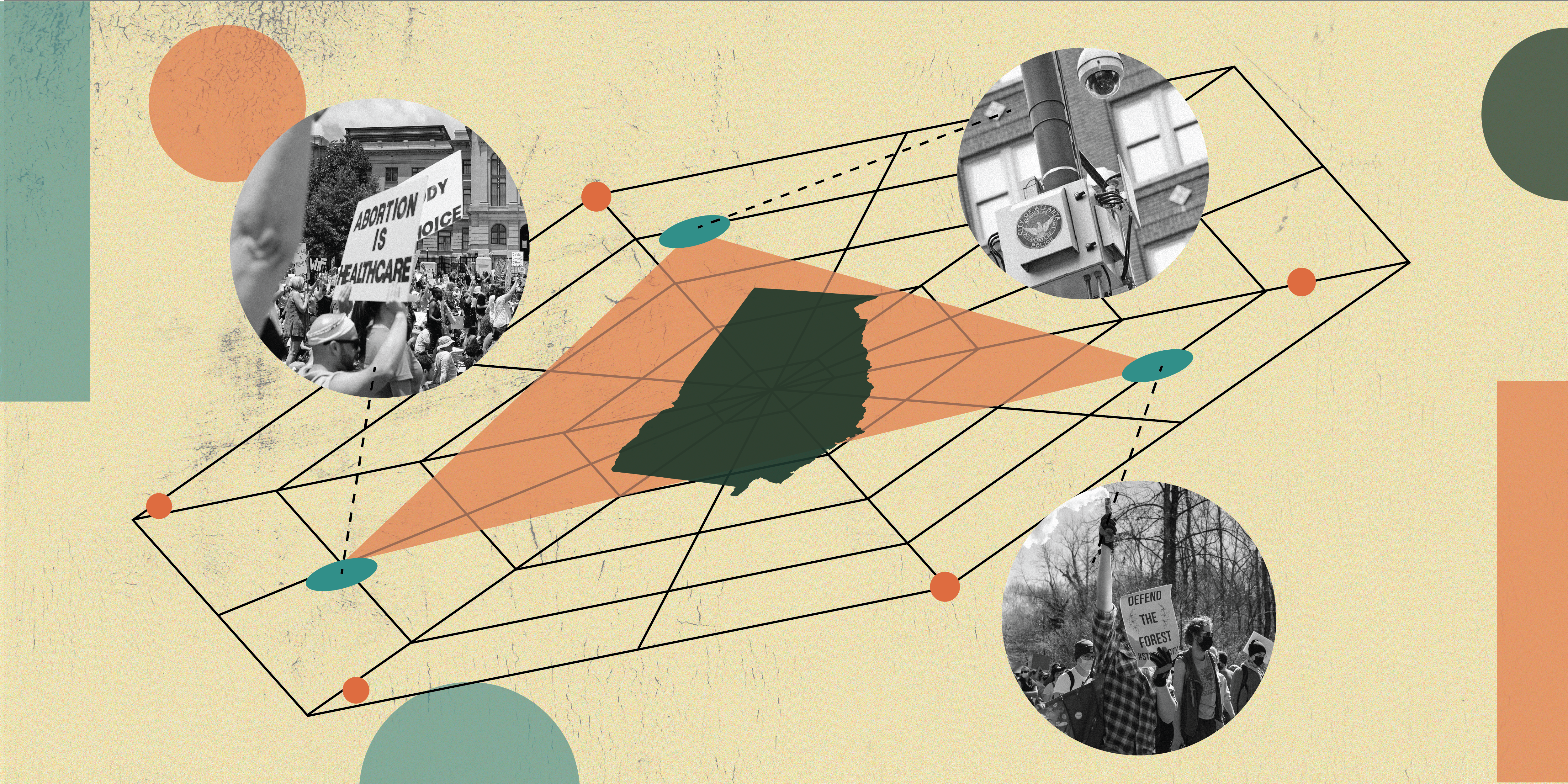

The campaign started on Juneteenth 2024, and activists voicing the need for positive change are speaking up about how important this season is to the people of the South and America as a whole and why the “Summer of Resistance ” is the precipice of activism in the city.

“Black and Brown working-class communities in Atlanta deserve to live free of police brutality and harassment,” organizers said in a publicly released media statement. “We deserve to have high-quality neighborhood schools, free after-school programs for our children, and quality grocery stores. We deserve better public transportation, safe and affordable housing, and well-paying jobs.”

“These Black people who thought they had the right to laugh, to be themselves, to be out, and you had white people immediately pushing back on that, wanting to police them.”

– Dr. Corrie Claiborne

Instead, the politicians in this city are fighting against this vision. As they have since the 1960s, Atlanta’s Black mayor and the city council are investing our tax dollars in programs and policies that make corporations and CEOs richer, at our expense.”

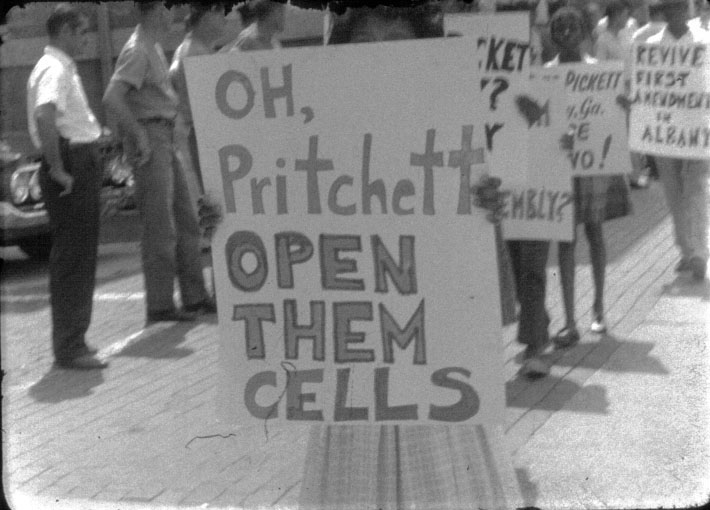

Dr. Corrie Claiborne, an English professor at Morehouse University, specializes in American Civil Rights Movement Literature and digital humanities. In a conversation with The Peach Pit, she details pieces of history of the American South and how it has bred the movements that have led to the Summer of Resistance. “It [seemed like it] was every summer that people were rising up,” said Dr. Claiborne. “It usually started off with a white person killing [someone] or soldiers coming back from World War I or World War II. These Black people who thought they had the right to laugh, to be themselves, to be out, and you had white people immediately pushing back on that, wanting to police them.”

For decades, Black activists, specifically in Atlanta, have led the charge for change, and each generation has passed the torch to the next. For example, students were inspired by the Montgomery bus boycotts and the North Carolina A&T sit-ins in the 1960s. Black student activists in the Atlanta University Center(AUC) gathered together to form a coalition between several colleges to push for an end to segregation. From 1940-1970, Atlanta was known as “the cradle of the Civil Rights Movement” because leaders such as Martin Luther King Jr., Congressman John Lewis, and others contributed greatly to the struggle against racial discrimination through activism in Atlanta and the global South.

Each decade brings another wave of protests and resistance movements that are either pioneered or greatly powered by Black activists, and the 2020s have shaped up to be no different.

“All movements [in this country] have been youth-led movements. Even the Underground Railroad was a youth-led movement,” Dr. Claiborne mentioned over Zoom with TPP. “Harriet Tubman was twenty-seven when she escaped from slavery, Frederick Douglass was twenty-one…even with the Atlanta Student Movement, [they were] eighteen and nineteen years old practicing how to be hit in the head.

There are no movements without people who know that whatever system they find themselves in, that is not the system they have to be in.”

Currently, one of the biggest issues that has been the catalyst for activism in Atlanta is police brutality. There has been a strong anti-police brutality presence in Atlanta for some time, and the pressure against violence committed by the Atlanta Police Department has had some small wins, such as the disbanding of Atlanta’s often-rogue Red Dog Unit. Avid listeners of hip-hop created during the Dirty South Movement have heard mentions of the much-maligned group. With songs like Goodie Mob’s “Red Dog” and Young Jeezy’s lines about the unit in “J.E.E.Z.Y” and “Tear it Up,” the now disgraced group was infamous for violence and humiliation, they made a name for themselves in the world of Atlanta hip-hop. Considered by locals to be a rogue element of the APD, Red Dogs faced allegations of ambushing young men and excessive violence, according to lawsuits, affidavits, and community memos.

The group’s visibility reached far beyond the scope of Atlanta when officers with connections to the unit killed Jamarion Robinson, a 26-year-old Black man. The officers, reports show, shot Robinson, who was unarmed, between 50 to 76 times. Since the group was disbanded, the sentiment that there must be a change in standards of policing has only grown stronger throughout Atlanta and the U.S. as well.

“We call on all people of good conscience to stand in solidarity with the movement to stop Cop City and defend the Weelaunee Forest in Atlanta.”

– Defend the Atlanta Forest

Atlanta mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms delivered a major blow to the movement against police brutality in 2021; she announced that a new law enforcement training center would be built on the old Atlanta Prison Farm, right off of Constitution Rd. in East Atlanta. The project was almost immediately dubbed “Cop City,” and there has since been resistance on multiple fronts in an effort to halt construction on the project.

On one front, you have the “forest defenders” who have taken up space on the land to mitigate deforestation in the area. The movement’s request is straightforward, as Defend the Atlanta Forest states in their pledge, “We call on all people of good conscience to stand in solidarity with the movement to stop Cop City and defend the Weelaunee Forest in Atlanta.” Police counteraction to this form of protest led to Atlanta Police killing 26-year-old Manuel Esteban Paez Terán, who went by Tortuguita, who was shot 14 times while their hands were raised. After Terán’s death, on two separate occasions, two people were arrested in direct actions that took place in Midtown, where the activists chained themselves to bulldozers at a Brasfield and Gorrie contracted construction site.

On the other hand, activists have also been vocal about the forest’s importance and how the land, whose native name is Welaunee Forest, is crucial to Atlanta’s tree canopy and flooding process. The land is considered one of the city’s four “lungs” as it provides highly necessary cooling and flooding regulations for Atlanta.

This summer, the meaning of resistance meant that activists are still demanding that the decisions surrounding Cop City be halted immediately. After multiple water main breaks over the summer, which left residents and business owners without operable water systems for days, and the city’s dismissal of a petition for a referendum on the construction of the training center, community members have taken to the streets and social media to express their frustration with the use of Atlanta’s resources. The general message of the “Stop Cop City” hashtag is that people don’t understand how Atlanta’s water infrastructure can be so fragile while $120 million is being spent on the new center. This is only the latest reason why the center should not be built, activists argue, and the funds being used for the project should be diverted to the improvement of conditions for Atlanta residents.

Atlanta activists continue to debate and champion the dissolution of Georgia State University’s joint project called the GILEE ( Georgia International Law Enforcement Exchange) Program – this is directly related to a major pillar of the Summer of Resistance. “…In 2020, thousands of Black, Brown, and working-class people took to the streets to demand an end to the police occupation of our communities and the police murders of Black Atlantans,” organizers say.

Summer of Resistance is an invitation to reclaim that energy again and to continue the ongoing fight for our collective liberation, dispute the state’s attempts to suppress us. It is an invitation to do something for our people.”

The initiative, based in the Andrew Young School of Policy Studies, has an arm of the program that trains police officers in Israel. According to activists who have studied Atlanta Police’s counterterrorism tactics, the violence inflicted by Atlanta Police is directly linked to the violence that is carried out on Palestinians by the Israeli government. For example, in 2018, Jewish Voice for Peace (JVP) published a report that connected Israeli training to excessive tactics used by police in the United States. When speaking of trainees who returned to the U.S., the report stated that “upon their return, U.S. law enforcement delegates implement practices learned from Israel’s use of invasive surveillance, blatant racial profiling, and repressive force against dissent.”

“People are still thinking about what to do because the war is not over. People are still dying in Palestine. It’s unconscionable. Something has to be done.”

– Dr. Corrie Claiborne

Notably, there are Israeli officers who have trained in Atlanta – as residents fear the tactics used by the forces of both Atlanta and Israel will have stronger parallels if Cop City is allowed to be built.

Due in part to the history of police brutality and state-sanctioned violence in America, activists are demanding complete divestment of funds and resources from the state of Israel, as well as self-determination for the people of Palestine. Dr. Claiborne referenced this concern from community leaders, saying, “People are still thinking about what to do because the war is not over. People are still dying in Palestine. It’s unconscionable. Something has to be done.”

The history of Black organizers’ solidarity with Palestinians goes far beyond recent events such as protests and student encampments. One of the critical components of the Black Power Movement was the demand for a free Palestine. Organizers saw that there were similarities between American Jim Crow laws and Israeli apartheid laws.

At a time when racial injustice was already boiling over in America, activists were emboldened to express global solidarity with those who were being affected by colonialism and racism.

The most notorious example of this collective empathy was the connection between the Vietnam War and the 1967 Israeli aggression that annexed Gaza and the West Bank.

That same year, in the summer 1967 issue of the Southern Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) newsletter, communications director and newsletter editor Ethel Minor published a groundbreaking piece entitled “The Palestine Problem: Test your Knowledge.” Throughout the piece, Minor asked readers 32 “Do you know?” questions in call-and-response style prose describing the on-the-ground survival of 20th-century Palestinians under Israeli colonial rule. In its critical thinking of foreign policy, the article stood as a stark departure from the mainstream post-war sentiments of the Israeli-American global relationship.

This piece – while not indicative of any public policy of the Atlanta-based organization – was meant to “educate” SNCC Members on the issue but would soon become one of the early machinations of Black, organized support for the Palestinian people, deriving from the South.

“I expect this [current generation of activists] to turn up around [the conflict in Palestine],” Claiborne says. “Whereas my generation may or may not – a lot of them have. That’s not a conversation that is not going to just die.”

Since October 7, leaders in various institutions have created a chilling effect on those who want to speak out in the name of the right to life. Professor Claiborne says establishing circumstances where solidarity is treated as heresy requires a more creative and steadfast approach to organizing.

The Summer of Resistance is called “a time to build people power,” as Black and Brown people have come together as communities to try different methods of liberation, and they were met with disappointment and very little positive change.

“This idea that you can’t even talk about the desire for Palestinian people to live without being deemed anti-semitic is a part of this [conversation],” Claiborne opines. “…We’re just going to have to write more, speak more, and connect to activists [in the region] and be able to share our common story about land loss, about surveillance, about policing, [and] about dehumanization.”

The pressure to broker peace for the Palestinian people is growing on a global scale, and Atlanta’s activist movement is powered by international solidarity that is also gaining visibility.

Unlike the 1960s, when speakers and activists platformed Black solidarity, social media has provided everyday people a way to keep educating themselves and to get involved in helping Palestinians in whichever ways they can. The Summer of Resistance was no different, as people in Atlanta could find basketball games, field days, teach-ins, charities, and more events whose purpose was to benefit those who needed help in Palestine. On social media, anyone can find purpose statements on why so many different types of events are important to the campaign. In these statements, the Summer of Resistance is called “a time to build people power,” as Black and Brown people have come together as communities to try different methods of liberation, and they were met with disappointment and very little positive change.

“I think that youth have always said that ‘resistance is our legacy,’” Claiborne says. “They are absolutely right about that, and I am really kind of encouraged by what I see, especially by college-aged kids.”

Participants were encouraged to post and share their own experiences of solidarity and direct action if they could not make it to actions and events, as helping to uplift the platforms of Palestinians sharing their own stories is always an important act of solidarity.

If the momentum of past movements started or encouraged by Black organizers in Atlanta is any indication of what the Summer of Resistance will do, it may be safe to say that many people will be educated and energized by the events under its banner. However, this campaign’s effects on the material conditions of those who choose to participate are unpredictable.

“[SOR] is a grassroots effort organized by local Atlantans who want to create a city free from economic, social, and political oppression,” the statement continued. It is a call to the people of Atlanta and beyond to join us in the fight for a better future. It is an invitation to resist.”

Kierra Johnson

Kierra is a multi-hyphenate from Atlanta, Georgia. Politicized by the Black Lives Matter Movement, they got their first experience organizing with Malcolm X Grassroots Movement. Kierra graduated from Clayton State University with a B.A. in English with a concentration in Writing. When they are not doing advocacy work, Kierra likes to write stories and poems, one of which was long-listed for the Fish Publishing Short Story Prize for 2021/2022. They also cohost a true crime podcast called I Ain’t a Killa with friends in Atlanta.

0 Comments